As Elections Approach in Turkey, Erdogan’s Anti-Kurdish Rhetoric Fuels Repression

The delegitimation of pro-Kurdish politics is a mainstay of Erdogan’s rhetoric—and that of Turkey’s other right-wing parties. To build democracy in a potential post-Erdogan future, these discursive strategies must be understood and countered.

The results of Turkey’s May 14 parliamentary and presidential elections will be consequential for Kurds inside Turkey and abroad. Like the 2015 and 2018 campaigns, the 2023 election season has sparked a campaign of incendiary rhetoric, repression, and violence targeting the pro-Kurdish political movement and its candidates, as well as Turkey’s Kurdish population more broadly. Many right-wing political parties, including the governing Justice and Development Party (AKP)-Nationalist Action Party (MHP) coalition, have employed racist and delegitimating discourses targeting the Kurdish people and pro-Kurdish candidates in order to win support from nationalist voters. This naturalization of anti-Kurdish racism through official discourses aggravates the hostile atmosphere in the country and provokes violent attacks targeting pro-Kurdish politicians and activists.

Since the success of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) in the June 2015 parliamentary elections, the breakdown of peace negotiations between the government of Turkey and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) around the same time, and then-prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s subsequent alliance with the far-right MHP, Kurdish politicians and HDP branches have suffered from extreme levels of state-sponsored violence and judicial oppression as well as attacks by individuals unaffiliated with the state. This violence is accompanied by racist discourses.

In this oppressive atmosphere, a closure case against the HDP was filed in March 2021. The initial case was rejected after just two weeks. This decision resulted in fierce criticism from the government, including MHP leader Bahceli’s public call for the closure of the Constitutional Court. The Court accepted a second iteration of the indictment in June 2021. Since the HDP’s petition to postpone the case until after the elections was refused, the party opted not to run in the elections under its own name. As a result, pro-Kurdish candidates are participating in this election on the Green Left Party (YSP) lists. This resulted in the party losing its right to participate in balloting committees, increasing the chances of potential electoral fraud in highly militarized Kurdish cities. Moreover, YSP branches are suffering from violent attacks prior to 2023 elections, including attacks targeting the party branches in Turkey’s three most populated cities.

I argue that these state-sponsored attacks are linked to structural racism, which is itself reproduced by political discourses that delegitimate of the pro-Kurdish political movement. My aim in this text is to present and problematize these anti-Kurdish political discourses, briefly the underlining main discursive strategies and cultural references that legitimate structural racism and anti-Kurdish policies. I will also lay out the differences in how opposition parties engage—or choose not to engage—in these discourses, and will subsequently suggest possible ways in which the situation can be improved in the near future in the case of a change of government.

Erdogan’s Discursive Strategies

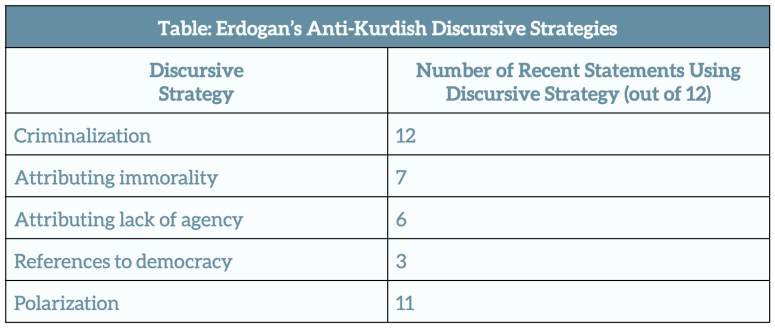

Erdogan and his government have continuously used several discursive strategies to delegitimate pro-Kurdish organizations and to legitimate violence against pro-Kurdish political actors. This has been a long-standing pattern since 2015. The official webpage of the Turkish Presidency features twelve reports on Erdogan’s public statements between 5-17 April in which Erdogan targets pro-Kurdish political parties, i.e. the HDP and the YSP. Analyzing these statements yields important information on how he delegitimates pro-Kurdish politics.

Criminalization

Erdogan’s principal discursive strategy in these public addresses was the criminalization of legal pro-Kurdish organizations. The most frequent reference made for criminalization was terrorism. This accusation occurs in all of the speeches examined. Some examples are accusing pro-Kurdish HDP politicians of being a branch or an extension of ‘terrorists’ in the parliament or directly calling them ‘terrorists’.

Groundless murder accusations constitute another common form of criminalization. These claims often target imprisoned former HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtas. In many of his public addresses, Erdogan accuses Demirtas of killing 51 Kurdish people, a claim unsupported by any facts. Erdogan is referencing the clashes between pro-Kurdish youth groups and Islamist youth groups in various cities during the ‘Kobani protests’ in October 2014, during which 46 people were killed. Most of the murdered protesters were supporters of the pro-Kurdish political movement. The protests were sparked by Erdogan’s comments that implied support for the Islamic State (ISIS) during the siege of the Syrian Kurdish town of Kobani.

Erdogan repeats similar accusations targeting the HDP as a whole in other speeches: for example, stating that ‘these are murderers, these are terrorists’ in reference to HDP members. In the same speech, Erdogan also accuses HDP politicians of being ‘hired assassins.’

Criminalizing the pro-Kurdish political movement legitimates excessive state violence and oppression. It also legitimates violence by other actors. By criminalizing a political movement, it is possible to present them as public safety threats and further social polarization based on the ‘friend-enemy’ dichotomy. The criminalization of the HDP results in its enemization, provoking feelings of hostility and hatred in conservative or nationalist sectors of the society. As a result, dialogue and negotiations with the HDP (or other pro-Kurdish political actors) are considered impossible by a considerable portion of the society. This, in turn, leads to a perception that violence is the only means by which the Kurdish issue can be addressed.

Attributing Immorality

Erdogan’s speeches also use moral discourses to cast the HDP as an immoral actor. References to perversion, self-seeking and inhumanity, and lack of authenticity and sincerity are among the examples of this pattern. By accusing the HDP of immorality, pro-Kurdish politicians are considered untrustworthy, which also furthers the polarization among ‘us-others’ based on the dichotomies of ‘friend-enemy’ and ‘good-evil’. Evilness-implying references are especially dangerous since these can justify the destruction of the ‘evil’ not just as a legitimate action, but also as a moral duty.

References to democracy

Erdogan also references ‘democracy’ in order to accuse the HDP of being ‘un-democratic.’ This includes calling the HDP an ‘enemy of democracy’ and stating that they (Erdogan’s government) will defend democratic achievements. By accusing the ‘other’ of being an enemy of democracy, anti-democratic practices can be legitimated in the name of democracy itself. This is similar to how state violence can be legitimated in the name of ‘nonviolence’—which means legitimating violent acts by arguing that they prevent greater violence. Erdogan’s claims that the HDP are ‘servants of imperialism’ or are being supported by ‘imperialist powers’ have a similar function. These accusations work to consolidate the enemization of the HDP and to underline its character as a threat to public safety.

Attributing lack of agency

Arguing that the HDP lacks agency is another discursive strategy that aims to delegitimate the legal pro-Kurdish political movement. The examples include the accusation that the HDP receives orders from the PKK, which implies that the legal political party does not have agency of its own. Lack of agency arguments instrumentalize and dehumanize HDP officials and imply that establishing dialogue and negotiations with them is not necessary. Thus, this argument works to discredit and delegitimate the HDP.

Other polarizing comments

Inciting polarization appears to be a conscious discursive strategy employed by Erdogan. While one such example is omitted from the official website of the Presidency, it is still important to mention to demonstrate the level of polarizing remarks in his speeches: ‘we are as Turkish as they are Kurdish’. Such comments stress on the dichotomy of ‘us-others’ by inciting racial tensions within the country.

Examples from other government actors

Erdogan is not the only official to use these discursive strategies. Other members of the AKP, as well as politicians from the AKP-led electoral alliance (the People’s Alliance) resort to these strategies when targeting the pro-Kurdish political movement.

For example, Interior Minister Suleyman Soylu has stated that the HDP was a serious threat to the country and accused the party of funding ‘terrorists’ while criticizing the Constitutional Court for having not yet banned the HDP. This is an example of criminalization of the pro-Kurdish legal political movement. Mevlut Cavusoglu, Minister of Foreign Affairs, claimed that the actions of the HDP were determined by the PKK, thus accusing the party of lacking agency.

Devlet Bahceli, leader of the second largest political party of the People’s Alliance (the MHP) also targeted the HDP on several occasions during the last month. Bahçeli accused the political parties of the Labor and Freedom Alliance, including the HDP and YSP, of immorality. He labeled them a threat to the future of Turkey and criticized the opposition for supposedly being allied to ‘hired gunmen of global imperialism’. In an instance of criminalization, he called Demirtas a ‘terrorist’ and the HDP ‘the nest of (…) murderers’. In another public speech, Bahceli linked the HDP to terrorism and accused it of being controlled by external powers, which is an example of attributing a lack of agency.

Another political party that participates in the elections under the People’s Alliance is the Islamist New Welfare Party (YRP). Its leader, Fatih Erbakan, also targeted the HDP and YSP in the last month. Erbakan described the HDP as a threat to election safety during a public interview and accused the HDP and YSP of secrecy and irreligiousness, attributing immoral traits to the pro-Kurdish political movement. Another minor political party in the alliance is the nationalist-Islamist Great Unity Party (BPP). BPP leader Mustafa Destici accused the HDP of being the representative of ‘terrorists’ and called HDP politicians ‘traitors’—examples of criminalization and immorality-attribution based on nationalist values. In a video that he shared on Twitter, Destici again argued that the HDP is linked to ‘terrorism’ and ‘warned’ the social-democratic Republican People’s Party (CHP) and its Nation Alliance to not to accept the HDP’s support for their presidential candidate.

The Erdogan-led People’s Alliance constantly uses rhetoric that criminalizes the pro-Kurdish political movement and attributes negative qualities like immorality and lack of agency to it. In their public discourses, these political parties aim to intensify existing political polarization, which helps them consolidate nationalist support and discourage the main opposition from acting together with the pro-Kurdish political movement.

THE Nation Alliance

The pro-Kurdish political movement is unofficially supporting CHP leader Kemal Kilicdaroglu, the presidential candidate for the opposition Nation Alliance, in the elections. Demirtas, who remains the most popular politician among Kurdish youth after 6.5 years of imprisonment, has declared his support for Kilicdaroglu multiple times. Notably, the YSP is not fielding its own presidential candidate.

Kilicdaroglu rarely addresses the topic of the HDP. When he does, he does not criminalize the party and its voters. Recently, he posted a video to his Twitter account criticizing the fact that millions of Kurds are being treated as if they are ‘terrorists’ in Turkey. Kilicdaroglu also met with HDP co-chairs Mithat Sancar and Pervin Buldan on March 20, where he criticized the appointment of trustees instead of elected pro-Kurdish co-mayors in almost every municipality where pro-Kurdish candidates won the local elections in 2014 and 2019. He has also criticized the closure case and stated that the Turkish state must respect the Kurdish language, making reference to the exclusion of Kurdish language in the parliament. CHP parliamentary group deputy chair Özgür Özel also recently criticized the attacks targeting the HDP and what he called its ‘demonization’.

This strategy makes electoral sense. The pro-Kurdish political movement indirectly supported CHP candidates in 2019 by not putting forward candidates for city mayors in some major cities, which led to historic AKP losses in Istanbul and Ankara. Kurdish voters are expected to play a similarly decisive role in the upcoming election.

The situation is similar for most of the smaller right-wing political parties that will participate in the elections on CHP lists. Ali Babacan, leader of DEVA (Democracy and Progress Party) and a former AKP official, had criticized the unlawful treatment of Demirtaş. The other three right-wing parties have also refrained from publicly discrediting the HDP during the last several months—although some of them, especially the DP (Democrat Party), have previously engaged in such discourse.

By contrast, the CHP’s largest ally, the far-right nationalist Good Party (IYIP), is a major contributor to discourse that delegitimates the pro-Kurdish political movement. The party was established by politicians that left MHP after an internal divide. It is participating in the parliamentary elections as part of the Nation Alliance, but with its own candidate list. IYIP group deputy chair Erhan Usta had stated that their aim was to put forward a presidential candidate who would not be supported by the HDP as recently as March 2023. IYIP vice president Musavat Dervisoglu accused the HDP of terrorism in a public interview on April 20. Similar accusations have been frequently made by IYIP politicians since its foundation in October 2017.

Other opposition parties

Pollsters have identified two political parties outside of the three main alliances that may receive more than one percent of the vote: Muharrem Ince’s right-wing Homeland Party (MP) and Umit Ozdag’s far-right anti-immigrant Victory Party (ZP). While Ince is one of the four presidential candidates, Ozdag’s party supports the fourth presidential candidate, far-right nationalist Sinan Ogan. Both parties have resorted to discursive strategies that delegitimate the pro-Kurdish political movement.

Ince, in an attempt to discredit the HDP, made a sexist comment, stating that it is as legitimate to ask for HDP votes as it is to ask for votes in brothels. This analogy was supposed to attribute immorality to the HDP, which resonates with a portion of nationalist conservatives in the country. He also stated that any political party that would not call PKK ‘terrorists’ is illegitimate, trying to criticize the CHP for receiving the HDP’s support in the presidential elections.

Ozdag and his party have produced an extremely racist discourse targeting the pro-Kurdish political movement. ZP has borrowed rhetoric from European-style neo-Nazi movements, constantly targeting immigrants and Kurds. Ozdag himself has been visiting YSP booths to provoke the party’s supporters. In one case, he told a young woman from the HDP that he was surprised that she does not look like a ‘murderer’ given her party preference. On another occasion, he made a joke with terrorism references when he found an empty YSP booth. Ozdag has also repeatedly compared Kurds to animals, calling the YPG the ‘biggest dogs of the Middle East’ to imply immorality and lack of agency and calling HDP members ‘jackals’ to attribute immorality.

Conclusions

The pro-Kurdish political movement is constantly delegitimated by political discourses led by ruling officials and far-right political parties. The most frequent discursive strategies are criminalization and the attribution of a lack of important human traits like morality and agency. These discourses aim to consolidate political polarization in the country, presenting the pro-Kurdish political movement as the ‘other’ and as the ‘enemy’ and thus legitimating violence and repression against them. These statements dehumanize pro-Kurdish politicians, undermining the prospects for constructive dialogue and negotiation in Turkey.

While ideologically not receptive to the pro-Kurdish political movement’s demands, the CHP and Kilicdaroglu seem willing to promote dialogue and refrain from making comments that would delegitimate pro-Kurdish politicians. This can be considered an improvement for Turkey considering the historical invisibilization of pro-Kurdish politicians. However, years of criminalization, enemization, and dehumanization are difficult to overcome–even in the case of a favorable electoral outcome.

If a new government in Turkey seeks to create culture of peace and democratization, discourse that re-humanizes the Kurdish people and re-legitimates the pro-Kurdish political movement in the eyes of the majority of the population will be necessary. Examining the discursive strategies that lead to polarization and delegitimation is important for understanding how these processes can be reversed. It will be crucial to produce and promote discourses that legitimate the pro-Kurdish political movement as a moral and rational political actor, with whom it is possible to negotiate and work with in order to overcome Turkey’s ongoing sociopolitical inequalities and the structural racism that has existed since the country’s foundation.

In a context of economic and political failure, the government provokes identity-based tensions and consolidates political polarization with the hope that this will secure votes from the majority Sunni-Turkish population of the country. Their aim is to receive votes despite their failure by presenting the elections as a fight against a dangerous, otherized enemy. To this end, they have also started provoking verbal and physical attacks targeting CHP politicians and branches, using similar discourses to those that have incited violence against pro-Kurdish political parties in the past.

The most important thing that can be done by international and transnational actors at this moment is to condemn all acts of violence and violence-inciting rhetoric from the ruling political parties, which could lead to cases of violence targeting the pro-Kurdish political movement and the candidates its supports.

(Photo: Ozan Guzelce/DIA images via Getty Images)